![Two wooden trestles, constructed and installed by the hall’s caretaker Wang Changfa, hold up the front corner of the damaged Mingxian Hall. Wang says he hopes “someone will take [the hall] away from me and repair it properly.”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54a60e81e4b01e05d9a86578/1420173221588-ZYLG91NNYVYCK8OJN44L/06-20130909-Bishan-0798.jpg)

Historical Value: A Chinese Town Appraises Its Past

The once-grand entrance of the Mingxian Hall is locked and hidden behind splinted boards and overgrown greenery. Wang Shouchang, a 67-year-old farmer from Bishan village, leads us into the cramped kitchen of the farmhouse next door and heads through a passageway on the far wall. What stands before us is breathtaking: a soaring space whose ruined grandeur is only made more compelling by the way it has been packed to the rafters with the humblest of everyday junk. The hall was built in the late-Qing dynasty by the Wang family as a place to venerate a relative who served as a high-ranking civil official in the imperial court. Since the 1980s, the Mingxian Hall has been a makeshift communal storage space, littered with cast-off toys, aged farming equipment, and pre-ordered coffins, which compete for space with a pair of pigs and a flock of boisterous chickens.

Bishan, in the historic Huizhou region of Anhui province, once boasted 36 such Wang family halls. Today, two centuries and a revolution removed from its most flourishing period, only three halls remain. As China’s economy soars, an exodus from the countryside into nearby towns and cities hastens Huizhou’s detachment from its past.

Nearby villages better endowed with historic architecture were granted UNESCO world heritage status in 2000 and have been overrun with tourists and film crews ever since. Their success puts also-ran villages in the region, like Bishan, at once closer and further away from the fruits of China’s new prosperity. Tourists—at least the fast-moving tour-bus variety—can visit only so many places in a day.

But Bishan’s relative lack of touristically exploitable cultural heritage has recently given it a different kind of allure and possibly, a second chance at escaping obscurity. Ou Ning and Zuo Jing, two urban cultural figures, have settled in Bishan and are attempting to revitalize its economy and cultural heritage without resorting to mass tourism. Their Bishan Project, which we have been documenting for the past year, has brought more rarefied forms of development—an arts festival, high-end rustic-chic guesthouses and a branch of the Nanjing bookstore Librairie Avant Garde—to Bishan, all in an effort to explore routes to economic revitalization that don’t involve industrialization or mass tourism.

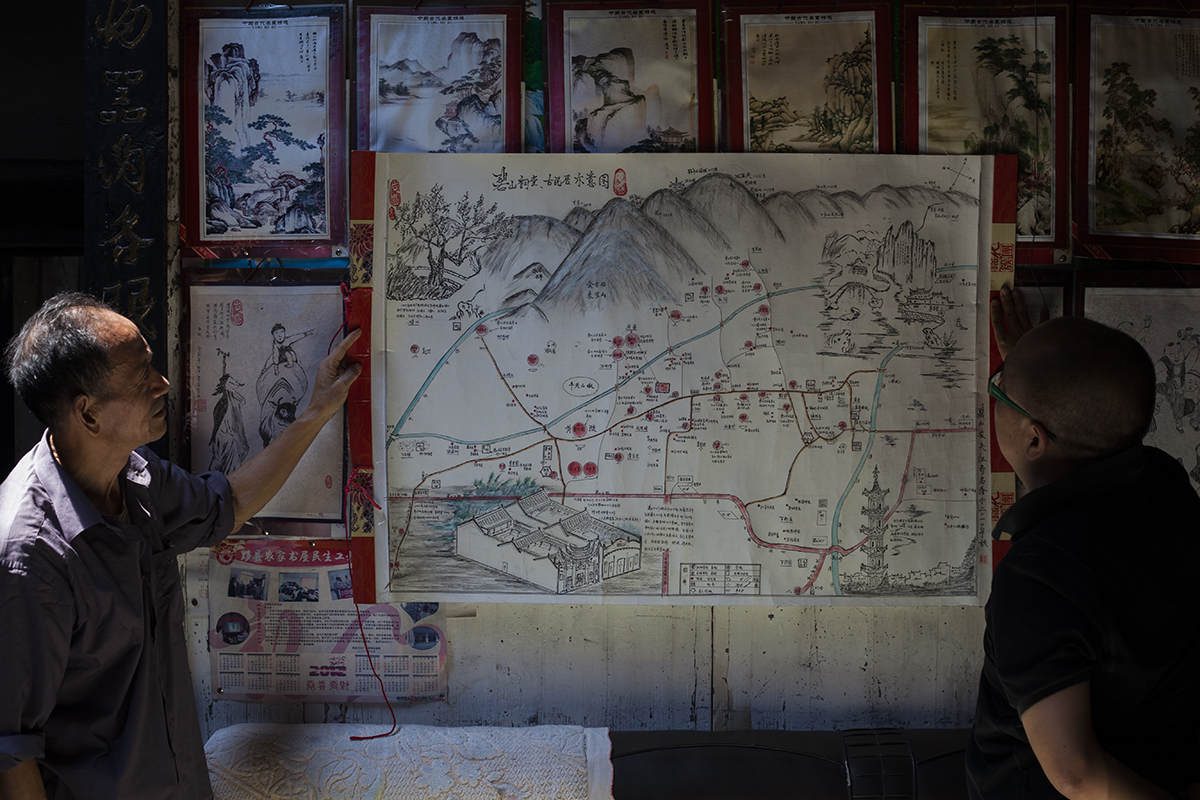

Unlike most villagers, Wang Shouchang maintains a deep connection to Bishan’s illustrious past. He devotes much of his private time to researching the kinship history of the region. Scenes he has drawn of Bishan and its surrounding mountains cover the walls of his home. When we visit his house, he unfurls a hand-drawn historical map of Bishan that shows the village before the ravages of the Taiping Rebellion and the Cultural Revolution stripped it of its most distinctive features. He has signed it, “Wang Shouchang, Wang Family 93rd Generation.” Wang knows that even if Mingxian Hall were fully restored, no one would use it for worship—the village’s traditions have crumbled faster than its buildings. But, a combination of local and family pride and dismay at the idea of letting the town’s rich “cultural deposits” go unmined has Wang hoping tourism will grow.

If that happens, Mingxian Hall will likely get a facelift, so that busloads of visitors can bask in the artificial glow of its imperial glory days. If Bishan’s urban immigrants repurpose it, perhaps it will take the village in a new direction. But so far, the hall remains in shambles—with its grandeur and the hardships it has weathered in plain view.

Historical Value: A Chinese Town Appraises Its Past

ChinaFile, January 10, 2014

恢复徽州碧山村的旧日风华

The New York Times Style Magazine (Chinese edition), March 6, 2014

Images and text by Leah Thompson

"Why Defenders of Killer Whales Are Worried About China," ChinaFile, May 29, 2014.

"There Goes the Neighborhood: Will a new craze for historic houses help protect China’s cultural heritage—or do just the opposite?" ChinaFile, April 11, 2013.

"迁建,徽州古建保护的下策?" The New York Times (Chinese edition), April 22, 2013.

"Unlikely Harvest: An Arts Festival in Rural China Beats the Odds," ChinaFile, December 17, 2012

"一个被官方取消却又意外成功的中国乡村艺术节 - 纽约时报中文网 国际纵览,"

The New York Times (Chinese edition), January 7, 2013

A Map of China’s Back-to-the-Land Efforts, ChinaFile, December 15, 2014.

Courtesy of Russian Orcas Facebook Page